My knowledge about the digital world is admittedly limited, but one thing I’ve come to realize is that being “profiled” online isn’t always a bad thing. Thanks to my occasional likes and shares on social media, I’ve found myself pleasantly surprised by the content the algorithms have been sending my way — and this time, it’s something truly special.

Out & About Investigating

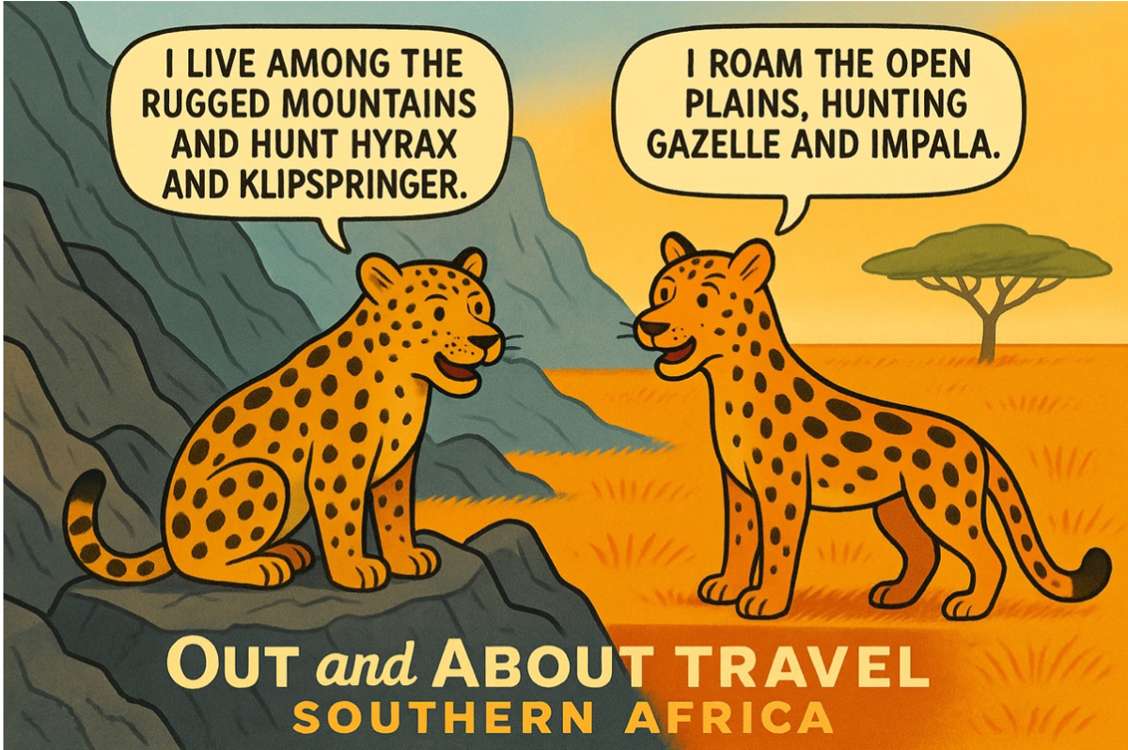

Read between the Spots

Cape Mountain and Savannah Leopard

In the shadowy stillness of the savannah, a ghost slips through golden grass sleek, bold, and built for speed. But far to the south, where mountains cut the sky and the fynbos clings to stone, another leopard moves stockier, secretive, and silent as mist. Two predators, same species, worlds apart. This is the story of their divide.

Cape Leopard vs Savannah Leopard: Southern Africa’s Spotted Giants

Nestled high in South Africa’s Cape Fold Mountains, the Cape Leopard this elusive mountain cat is the same species (Panthera pardus) as the familiar savannah leopard, but centuries of isolation have made it smaller and highly specialized.

Cape males average only about 35 kg (females ~20 kg)– roughly half the weight of Savannah males (60–70 kg) and females (35–40 kg).

A Cape leopard will usually vanish into the mountainous terrain or brush long before a human could get close.

Cape and savannah leopards occupy very different homes.

Savannah leopard lives in warm dry bushveld and woodland.

Physical Traits and Behaviour

Apart from size, the two leopards look very similar – coat colour and rosette pattern show no obvious sharp differences. Both have the stocky, strong bodies and powerful jaws. All leopards are solitary and largely nocturnal hunters.

They scent-mark and roam alone at night, communicating by roars or rasping growls. In the cool mountain air, Cape leopards sometimes move at dawn or dusk, but they also favour nighttime. Savannah leopards are similarly secretive.

In both habitats the leopard’s climbing skill is legendary. They are arguably the strongest climbers of the big catsMales (and even females) will heft an ungulate kill up a tree branch to keep it from hyenas or jackals. Cape cats hauling a duiker kid into a hakea bush, and Kruger leopards dragging a young impala up an acacia.

Diet and Hunting

Leopards are opportunistic carnivores, but prey choices reflect habitat. Cape leopards mainly hunt rock hyraxes (dassies), klipspringer and grysbok antelope, porcupines, and the occasional aardvark or young baboon. Typically their prey weighs under 20 kg. In dry seasons, Cape leopards will also scavenge dead sheep or livestock – not by preference, but due to prey scarcity.

Savannah leopards in contrast prey on larger and more varied quarry. Their staple is medium-sized antelope (20–80 kg). Impalas (adult and fawn) often top the list, with Thomson’s gazelles, warthogs and small antelope (dik-dik, steenbok, reedbuck) also common. A prudent leopard may even tackle young wildebeest or buffalo calves.

Both leopard types will eat birds, rodents, or reptiles when hungry. But for example, Kruger leopards have been seen preying on baboons, bushpigs, and occasionally the calves of zebra or wildebeest. Unusual victims like small kudu or even a young giraffe are almost exclusively a savannah phenomenon.

Home Range and Movement

Cape leopards roam across huge territories. In the wild Cape mountains, a male leopard’s home range can be 200–1,000 km². He’ll patrol rocky ridges, cliffs and ravines to find enough food.

By comparison, a male leopard in Kruger National Park usually confines itself to about 25–50 km² (females much less). In practice, this means Cape leopards may trek 10–20 km in a single night. One collared male (“Malcolm”) was recorded covering an incredible ~1,190 km² in a few months. The savannah leopard covers far less distance each night, but still marks overlapping territories with neighbours.

A consequence is that Cape leopards frequently cross private farmland and even public roads. Their broad patrols enable finding scarce prey but also expose them to human dangers. Savanna leopards, with smaller ranges, remain mostly inside large reserves or contiguous wildlands (though they too sometimes wander into settlements. (especially in areas where Reserves and parks border villages).

Encounters with People

Both leopard types are reclusive and avoid conflict. Cape leopards especially are known to be very wary of humans; they typically freeze or bolt at the first hint of danger. no unprovoked Cape leopard attack on a person has ever been documented.

Savannah leopards behave similarly in the wild: shy and alert. As one ranger quips, the only time a leopard “talks” to humans is by leaving paw prints on a car hood at night!

Livestock conflict differs between habitats. Cape leopards rarely target farm animals unless food is utterly scarce. If a sheep or goat is taken on a remote farm, it is usually an opportunistic kill (often blamed on leopards but occasionally the real culprit is a jackal or dog).

By contrast, savannah leopards are more often labelled “problem animals”. Studies note that most reported leopard predation in Africa involves animals kept in simple night kraals.

Retaliation is common: frustrated farmers sometimes shoot or poison any cat seen near their stock. Conservationists therefore stress better husbandry (guard dogs, improved bomas) to keep livestock safe without killing leopards.

Habitat Differences and Viewing Spots

Cape Environment: The Cape’s fynbos mountains are fire-prone, nutrient-poor and steep. Vegetation is dense but low (heath and shrub), and true forests are rare (mainly protected kloof pockets). Leopards here use caves, hollow logs, and dense pine groves for shelter. Apart from the Cape leopard, few large predators remain: no lions unless in reserves.

For eco-tourists, the best bet to glimpse Cape leopards is via special tours or camera-trap projects. The Cape Leopard Trust (CLT) runs guided trips in the Cederberg Wilderness and Boland Mountains (Bainskloof, Grabouw area). Sightings can happen on remote mountain drives or even on hiking trails (though they are exceedingly brief). Besides Cederberg, small numbers roam places like the Swartberg and Jonkershoek reserves. (Local farmers on the Cape Peninsula and Overberg also report leopard tracks – indeed, “wild leopard” populations exist in nearly all the highland areas of the province.)

Savannah Environment: Here the leopards are widespread across the Southern African savannahs and woodlands. Kruger National Park (South Africa) is famed for them: over a thousand may inhabit the park’s 19,600 km². Other good spots include Hluhluwe–iMfolozi (KwaZulu-Natal), Phinda and Thanda reserves (Zulu coast), and Pilanesberg and Madikwe ((North Western South Africa)

Further afield, they thrive in Namibia’s Etosha National Park and Botswana’s Okavango Delta, and even in the more arid Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (where they share dunes with brown hyenas). Another hotspot for leopard sightings is South Luangwa Park in Zambia.

Tourists often see savannah leopards in daylight resting classically on shady branches in trees, or enjoying a leisurely stroll on a road.

In all cases, the viewing style differs: in the Cape you’re lucky to spot one at night with a thermal scope, whereas in a safari jeep in Kruger it’s more often the leopard that spots you from an acacia above the road!

Conservation and Threats

All African leopards are classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN, meaning their overall numbers are decreasing. The Cape population is particularly precarious: fragmentation by farms and houses, plus roadkills and dog attacks, continually chip away at their numbers. Surveys suggest fewer than 1,000 Cape leopards remain. Illegal wire snares set for small game are a serious hidden killer. Invasive predators (dogs) and too-frequent fires can starve leopards by depleting prey or den sites.

On the savannah, threats are similar in cause if not in scale. Habitat loss (fencing, logging, agriculture) and a shrinking prey base (from overhunting and illegal bushmeat trade) have reduced leopard range by roughly 30% in recent decades. Retaliatory killings are common near farms, and trophy hunting still occurs under controversial regulations in some countries. Poaching for skins or body parts is less intense for leopards than for lions or rhinos, but it does happen.

The good news is many protection efforts are underway. In the Western Cape, the Cape Leopard Trust, SANParks and several NGOs focus on research and outreach. CLT advocates predator-friendly farming (guard dogs, donkeys and predator-proof kraals) rather than shooting the cats.

In Kruger and other savannah parks, rangers conduct anti-poaching patrols and support community projects. For example, local conservancies build sturdy enclosures for livestock and

offer compensation when losses do occur. International groups (like the African Wildlife Foundation) help fund GPS-tracking studies and assisted-breeding research to keep the genetic pool healthy.

Tourism itself is a big ‘protector’ of especially the savannah leopard. Reserves, private and national both know that leopard sightings are rare and thus a big draw card for guests.

By combining ecological science with boots-on-the-ground stewardship, South Africa aims to keep both its mountain cats and bush leopards thriving for the next generation of nature lovers.

Further Reading

South African Travel Newsflash

Share This Post